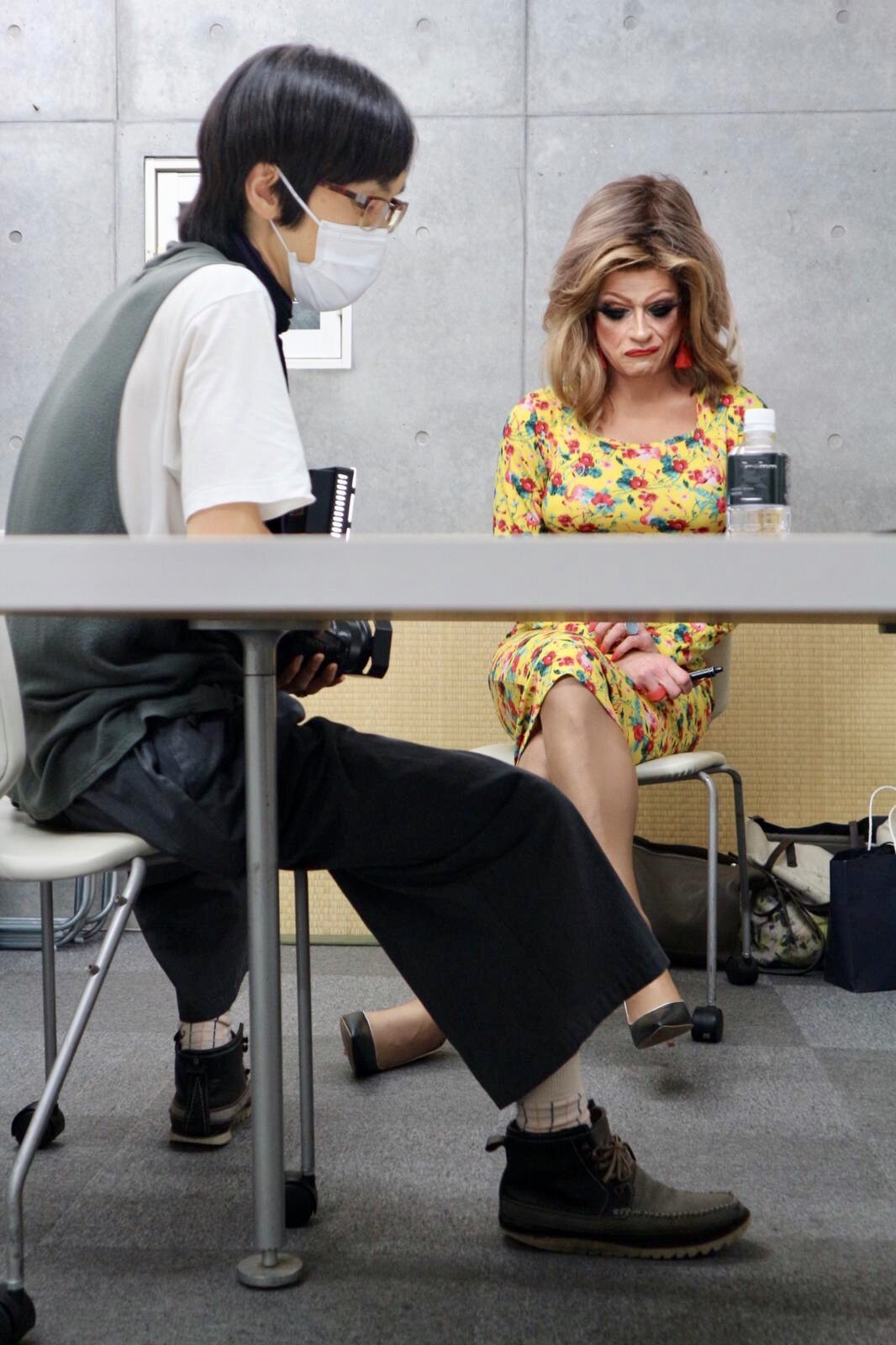

Panti Bliss is a pivotal, inspiring, figure in Irish society. The drag queen was a central, unifying, force behind the Marriage Equality Referendum which legalised gay marriage in the state in 2015. Her Nobel Call at the Abbey Theatre, which has been viewed almost 1 million times, relayed the painful inequality evident in everyday existence. She continues to be a dominant force for change and rights through her social media platform and radio show as well as being the owner of Panti Bar in Dublin.

Main image of Panti by Conor Horgan

Panti’s ‘Noble Call’ speech delivered on the stage of the Abbey Theatre, Dublin, on February 1, 2014.

Panti nominated her dear friend, the graphic designer Niall Sweeney, who has been a collaborator for many years.

I went to art college in the 80s mostly because I thought there would be other queers there. Disappointingly, there was only one.

Luckily for me, it was Niall Sweeney - and we’ve been best-gays ever since.

Apart from being the only other gay, Niall was also the college’s Star Student, because Niall is a bone fide design genius. Like all geniuses he possesses a spectacular and flashy talent, but he has an equally spectacular work ethic combined with a perfectionism that would drive a less talented person to insanity. He’s also obsessed with design. He eats, drinks, sleeps, and poops design. And then designs a better way to eat, drink, sleep, and poop design.

And even his poop would win a design award.

If he wasn’t so lovely and fun he’d be really annoying.

Work by Niall Sweeney

EX, a new collaborative film work, 2020

Directed by Niall Sweeney & Eamonn Doyle, Photography by Eamonn Doyle, Sound & Music by David Donohoe, Written by Kevin Barry & Niall Sweeney

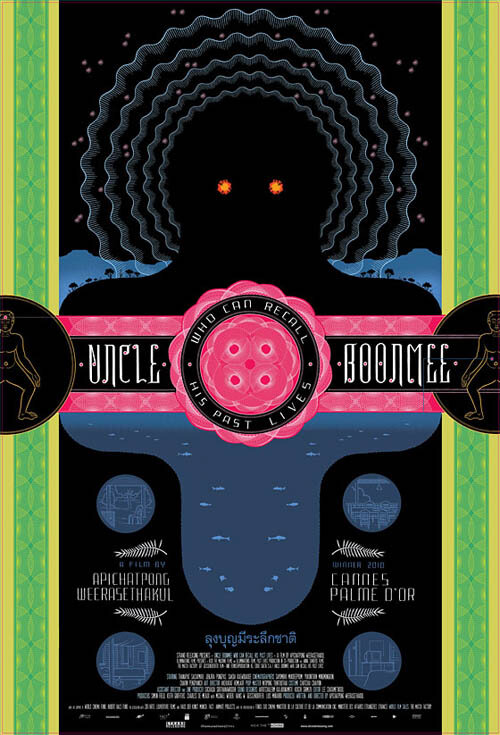

For Tomorrow For Tonight, Apichatpong Weerasethakul (IMMA, 2011)

Niall Sweeney nominated the award-winning Thai independent film director, screenwriter, and film producer Apichatpong ‘Joe’ Weerasethakul.

About 10 years ago, myself and Nigel started to get Skype calls at the studio from the jungle in northern Thailand. They were from the artist and film maker Apichatpong Weerasethakul. His film Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives had just won the Palm d’Or at Cannes. He was working on a new project called For Tomorrow For Tonight that would have its premiere at the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin. The museum had asked us to work on the design of the publication and, as is often the case, they entrusted us to work with the artist directly. “Everyone calls me ‘Joe’”, he said, and then he asked us to make “a beautiful book about darkness.”

A few days later we received some disks containing almost everything he had done to date as well as everything related to this new work — films, videos, hundreds of photographs, texts, drawings… a lot of things. Hidden amongst all of these were some photos of dogs in the jungle, but perhaps not the jungle dogs you might expect. Joe had a number of Boston Terriers sharing his life — as do we (at the time we had Ollie with us, and now we have Agent Cooper Black). Joe’s “little aliens”, as he calls them, had names like Godzilla, Vampire, King Kong, Draclula — cinematic goths at home in the dark jungle of Thailand. So we bonded through our spirit animals.

For Tomorrow For Tonight takes us on a journey up the Mekong Delta flood plains, flooded as a result of the electrical dams that run the length of the river from China to Cambodia. It is a work of transformation, of reincarnation, of the comfort of ghosts, of the half-light. Through it, Joe tells us that when you shine a light on something — torch light, disco light, cinema light, electric light — you bring into life, into the present, its past and future lives. He tells us that at the very darkest centre of the jungle, there is a flashing red beacon set to the sounds of a techno beat. The colour of the Mekong, he says, is from the millions of ancestors once cremated and now suspended in its currents, and each time the river floods, it deposits these ancestors throughout the land, and we build houses and hotels and karaoke bars and cinemas from this mud, and then we illuminate these buildings with electric light. While all the while, clouds of dark smoke rise in the distance beyond the trees.

“Joe tells us that when you shine a light on something — torch light, disco light, cinema light, electric light — you bring into life, into the present, its past and future lives.”

For Tomorrow For Tonight features his friend, the seamstress Jenjira Pongpass. At the time, she had been having operations on her leg after a motorbike accident, and we see her with aerial-like rods protruding from her leg. In the film they attach small lights to them and wire her up to the jungle. Joe tells a story of how he and Jenjira are walking in the jungle at night. They have to stop as her leg is in great pain. He shines a torch on it while she massages it to get the circulation going. Afterwards, they see floating retinal memory images of her limbs, guiding them through the dark.

On the outside of the book we made with Joe, a silhouette sits at the mouth of a cave. Across the surface is a line drawing, like cave paintings or star charts of dismembered constellations. It is a tracing that Jenjira made for us of her own legs, hands and arms, including the metal rods. She traced them out while sitting on the floor of her once-flooded workshop home in the jungle, using the paper she uses for her dress-patterns. When you switch the lights off, these limbs glow in the dark.

These ideas of darkness and light, of the inherent spirits in all things, of trans (in all meanings), of the ancestral mud of the dance-floor and the universal field that connects all things past-present-future, all vibrating to the rhythms of a cosmological techno beat, had (and continue to have) deep resonance with me, and particularly how he weaves these ideas through the sometimes-quite-alien narratives of his films and installations with a lightness of touch — quite literally with light itself. Truly inspiritus.

Read Apichatpong’s letter on cinema during Covid here.

Stills from his forthcoming film Memoria starring Tilda Swinton below.

Apichatpong Weerasethakul* nominates actor Sakda Kaewbuadee (Tong) who is also prominent in assisting refugees and migrants detained by immigration services.

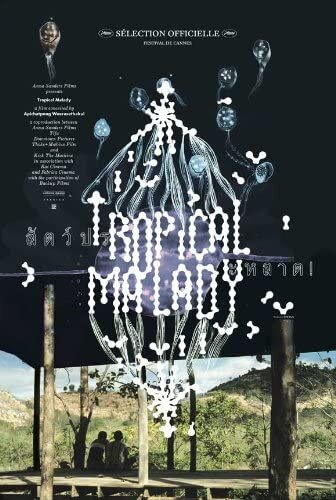

Sakda Kaewbuadee or Tong, appeared in several of my works. I first met him in 2003 when he came to our office for an auditon of Tropical Malady. He was from a farmer family in western province. He arrived in Bangkok a few years earlier and had worked in odd jobs such as a watch salesman, KFC employee, 7-11 clerk, among others. At his low point, he slept in the park and scavenged food from garbage. The man was fierce, resilient, and possessed an immense acting talent. Later, we went to Cannes Film Festival where I was moved to see him in the tux. Throughout the years I have witnessed this young man thrive and transform into a light of inspiration.

Tong met Laurent, his French partner in 2010. They have spent time between Bangkok and Montpellier. Tong learned French and started working for the underprivileged in Thailand. A few years back, he encountered stories of horrid situation faced by the refugees held at the Immigration Detention Center, or the IDC. These asylum seekers have fled from the war torn, religion conflicted, countries such as Pakistan, Congo, Somalia, and our neighbouring countries. As Thailand has not signed the 1951 Refugee Convention, these 1000+ detainees are not protected by the agreement that would ensure their safety and well-being. At the IDC, people are segregated into gender specific cells; families are parted; babies are jailed with their mothers; children over ten years old are separated from the families. A group of 70-80 people are crammed into a barren space so small that some of them stand sleeping. When a detainee ‘crosses’ an IDC warden, he or she risks being sent to a notorious cell where the light is always on. Tong told me a story of a man who had been locked up in the room for what seemed like a very long period. Inside, he couldn’t tell the time of day. Once he got out, two months later, something in him had been damaged. A sudden change of illumination tortures him, darkness hurts his eyes. To this day, even though he’s lucky to have immigrated to France, he must sleep with the light on.

“Throughout the years I have witnessed this young man thrive and transform into a light of inspiration.”

Tong regularly brings necessities to the detainees. His visit is the only way the family members can be reunited, in the visiting area. Tong has raised public awareness and inspired others to join his actvities. As he has learned more about the IDC’s inner workings, prejudice, (and issues that I cannot write here), Tong received threats. The authority wanted to silence his actions. But he persisted and widened his operations outside of the IDC.

Bangkok has around 6,000 illegal refugees living and working in the shadows. Some of them have family members in the IDC. Tong and his friends dropped foods in various spots in town even though they are aware that it is not the way to fix the system. They continue to support several people, especially the youngsters. Some of them hold secret jobs, some shuttered themselves in the rooms for fear of the immigration police. Discreetly, Tong took them to the park, to KFC for the kids’ birthdays. Sometimes he and Laurant took them to play badminton at a university where Laurant is working. He became a bridge to many families in and outside of the IDC. Some of them haven’t met one another for almost 10 years. Via their Facebook campaigns, so far Tong and his peers have helped five families find new homes in the other countries. It was an arduous tasks involving lots of paperworks and repeated visits to the embassies.

Last time I contacted him, Tong still drops foods during this Covid-19 pandemic. There are numerous activities and stories from Tong that I cannot do them justice in this space. I dream that one day Tong or someone would properly recount his experience and share it for his plight.

I often recall an early scene, a night scene from Tropical Malady. Sakda the country boy reaches up and fiddles with a fluorescent tube. The light blinks, turns on, and sheds a glow on his face. His eyes expressionless, his jaws firmed and fearless. I freeze this frame in my memory as a reminder of a life magnificently lived.

Apichatpong Weerasethakul May 23, 2020 Chiang Mai

*photo credit, Sean Wang

Sakda Kaewbuadee (Tong) nominates director Sompot Chidgasornpongse (Boat) who he first met on Apichatpong Weerasethakul's, Tropical Malady.

I first met Sompot Chidgasornpongse in 2002 when I was cast as one the main actors in Apichatpong Weerasethakul's film, Tropical Malady, which was also my first film.

Prior to that, I came to Bangkok looking for work, hoping to earn money to fulfill my dream as a university student. I worked various jobs; such as a builder, shopping mall staff, flower garland seller on the street, etc. Still, I couldn't gather enough money for my education. It was then that I met Apichatpong by the roadside while I was walking home. He asked me to come for an audition for a film. I later got selected for the role.

During the pre-production, Apichatpong also looked for more crew members. Many newly graduated students came to apply. Sompot was one of those who got a position.

While waiting for the actual shoot, I was also assigned as casting director, looking for more actors for other roles. I printed out announcement flyers to give out on the street. Sompot helped me with that, and with the actual audition process inside our office. He was also responsible for other tasks handed to him from Apichatpong. Soon after, he was promoted as our 2nd assistant director on the film.

Seeing him from the start, from his days as a regular intern, to the days when he quickly took on harder and more important responsibilities on the film, I couldn't help but admired him. I often mentioned Sompot to my close friend, so much that my friend was also impressed.

Another thing that I admired about Sompot was when our crew from aboard came to Thailand. Sompot was able to fluently communicate with the international producers and cinematographer in English. Sompot acted as our interpreter for the Thai team. He also helped me, because I couldn't speak English then.

We continued to work together on more of Apichatpong's films, until Sompot went to study in the US for his master degree in Film/Video. We drifted apart and lost contact.

As for me, after being an actor on more films, I finally had enough money to further my education. But from being away from it for so long, I lost the passion. I abandoned that dream until I met Sompot again when he came back to Thailand after his graduation. During our time apart, Sompot had continued working on other film projects, including his own short films and feature film. His works were successfully shown at various international film festivals. I felt as if he had some kind of magic.

“I lost the passion. I abandoned that dream until I met Sompot again when he came back to Thailand after his graduation.”

This made me think a lot about myself and the importance of education. Reaching the age of 40, I decided to pursue my study again with Sompot in mind. I couldn't continue my degree in the university, but I took special classes on computer graphic and web design, along with languages classes. Now I can speak both English and French, which lead to the opportunities of me working as supporting roles on two French films. All these happened because I got back to my education, thanks to Sompot as the inspiration.

Sompot and I now meet often at various events. We update each other about our lives today, and of course, we also talk a lot about our past memories.

Sompot Chidgasornpongse

on James Benning

Sompot Chidgasornpongse

on James Benning

Sompot Chidgasornpongse* nominates experimental filmmaker James Benning as a source of inspiration for him.

James Benning’s Listening and Seeing class was the most surprising class I ever took. Words were not required. In fact, the lack of words were requested. Every Friday James took us to a new landscape. The desert, the oil field, the mountain full of windmills, etc. We were left wandering by ourselves. We didn't talk to each other. We were there only to see and listen. To pay attention.

One Friday we met at 4.30am. From the foot of the hill, James led us, 10 or so students, up the path in the dark until we reached the top. We felt our way and sat down separately, barely seeing or hearing anything. We felt cold and tugged ourselves under the jacket we brought. Then we waited and concentrated on any slightest thing that could grasp our attention. The grass that we sat on, the wind, our own breathing and inner thoughts.

“James might be amused with my comparison, but I see him as a Zen master”

Gradually, some colors appeared in the sky. Dark blue, faint orange. The sound of the distance cars below. Clouds moved closer above our head. Their shadows passed us. Drizzle on our face and body. Then it rained lightly. The sound of the rain and more cars running down below. The sky glowed white with the sun ray on us. I could now see James and all my friends sitting quietly, observing. The surge of emotion erupted within me and I felt like my heart was bursting. There was no homework or assignment for this class. We didn't even have to talk about our individual experience being in those spaces. The experience was for ourselves to keep. James might be amused with my comparison, but I see him as a Zen master.

I cried watching his film Los (2000). It's a film that comprises of 35 static shots, each is 2 minutes and 30 seconds in length, filmed mostly in urban areas of Los Angeles. I cried not because there was anything particularly sad or heartwarming. Some might say that nothing really happens in the film (or in any other of James's films). I cried because James turned cinema into a portal. My being was in sync with the film's space and time the way I never felt from cinema before. I'm grateful that James had showed me what a rectangle frame filled with light can be, and what one person with a camera and a sound recorder can do.

*photo of Sompot by Kissada Kamyoung

Discover more contributors to Just Six Degrees such as Ali Smith, Eli Horowitz, Feld, Andrew Thomas Huang and Margrét Bjarnadóttir or search according to creative area of interest - design, sculpture, film, photography.